The Kid(‘s Parents) Are Not Alright

How the panic surrounding social media and smartphones distract us from a far more substantial cause of the youth mental health crisis

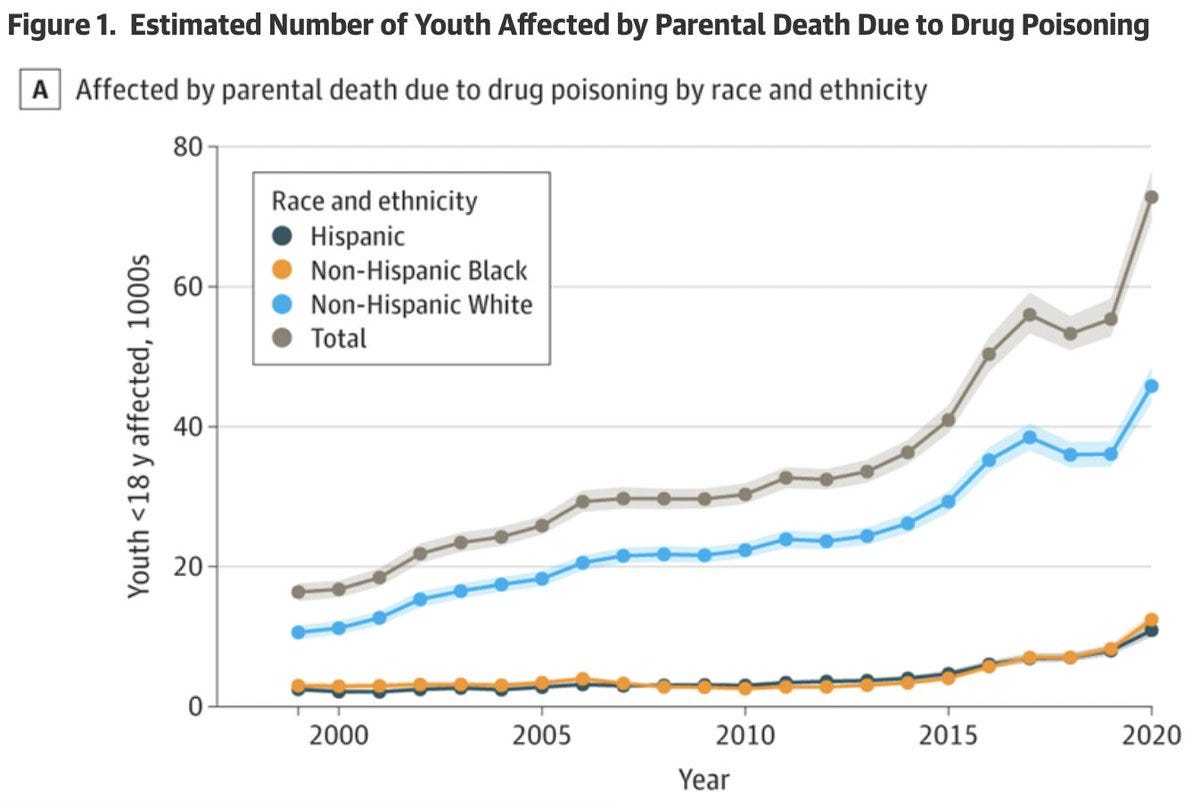

Two studies published in JAMA over the past week show that over the past 2 decades nearly 1.2 million US youth lost a parent to drugs or firearms, and the rate of parental death due to these causes increased most significantly in the past decade.

Additionally, suicides among adults aged 25-34 and 35-44, prime age groups for having young children, increased 38% and 25%, respectively, from 1999-2017.

Although the reasons for the recent rise in MH problems among youth in the US is undoubtedly multifactorial, I believe that the crisis among parents that has unfolded over the past 2 decades is the #1 contributor, far outweighing any putative effects that social media and smartphones have had.

Death of a parent is by far one of the worst things that could happen to a child, with far-reaching effects that are felt over many years and domains of life. There are the obvious direct interpersonal effects, which would create immediate acute psychological distress as well as long-term chronic psychological distress. And there are also immediate and long-term economic, social, and educational impacts. On top of all this, there are network effects that impact the family system immediately and over time. The mother that loses her partner, the sibling that loses his father, the grandmother that loses her son--all experience the loss personally and collectively as a family unit. So there's not only the huge direct effects from a parent's sudden death, but also the indirect network effects of the loss on the family system.

But there's no mention of this crisis in either of Jonathan Haidt’s or Jean Twenge’s hugely popular books claiming that social media and smartphones are the (primary) reason for the recent rise in MH problems among youth. Why?

Twenge recently wrote a blog post featured on Haidt's After Babel Substack that attempted to dismiss this alternative explanation by shifting the goalposts from deaths to self-reported mental health:

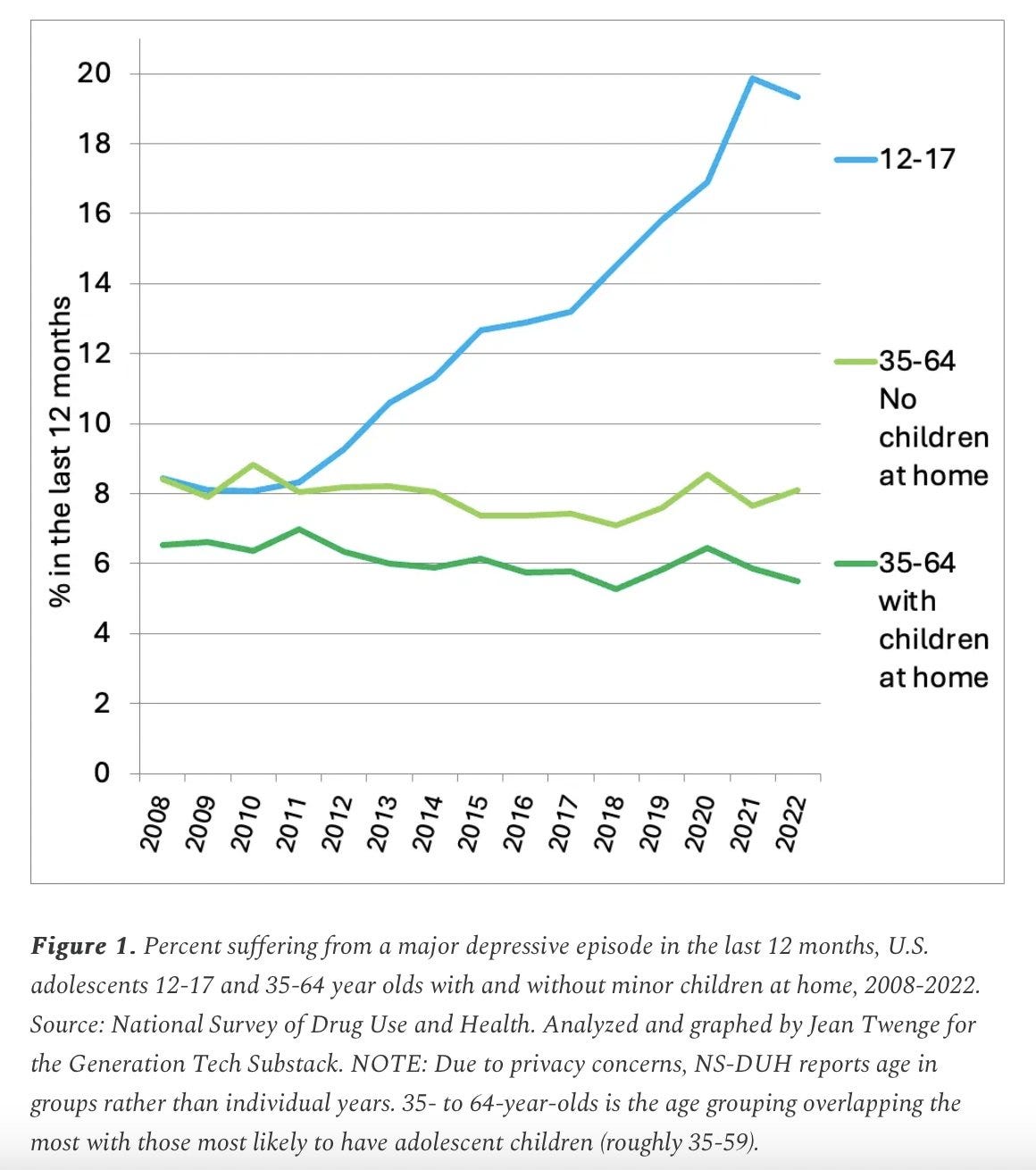

In suicide data, however, there is no way of separating the data by parents vs. non-parents. But we can examine depression, suicidal thoughts, and mental distress among parents with children 17 or under at home in the nationally representative National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH takes a cross-section of the whole population, not just those who seek help from doctors or therapists; thus, trends cannot be due to over-diagnosis or more willingness to get professional help.

Her reason for doing so was because parental status is not reported in death data tracked by the CDC. So, instead she shifted the focus to data from the NSUDH, a long-running, nationally representative survey that includes self-reported MH factors and parental status, among many other things. She found that rates of self-reported depression are much lower among adults aged 35-64 with children at home than among youth aged 12-17:

Despite the fact that the age grouping she uses is very broad, or the fact that parents younger than age 35 are suspiciously excluded from the graph, or the fact that self-reported rates of MH problems are prone to all sorts of well-known problems, Twenge takes this evidence as sufficient to dismiss the whole "parents are suffering and that's why kids are suffering" counter-argument.

I don't believe this post by Twenge is a genuine effort to take seriously what is a very serious and plausible counter-argument. To be fair, the recent studies I mentioned at the top of this post were published shortly after Twenge released her blog post, so she obviously could not account for them. However, using data from a single source1 to point out that self-reported rates of MH issues among parents are low and assuming that renders the whole counter-argument moot is more reflective of punditry than fulsome efforts at objective scientific argument. Now that these studies have been published and there is no longer an excuse to avoid directly engaging with the data on parental death, perhaps Twenge and Haidt can amend their earlier blog post to seriously deal with the implications of this counter-argument.

Further Reading

Many people have made this argument before me and much better than me. Check out this article by

and this article by Mike Males ().This is actually not true, toward the end of her blog post, Twenge includes a figure and a few sentences pertaining to data from a single year of the BRFSS, which also shows that MH is better among parents aged 35-55. Still, the vast majority of her post is devoted to the NSDUH data, and it’s unclear why Twenge only includes BRFSS data for a single year, especially when all the other figures in the post show trends over time.

You say you are a Data Scientist, so can you share some analysis? How about some regression work? I am really curious to see some correlations and where they show up. I keep reading all these articles, and they look like they are being written by journalists (random guesses with justifications). I would love to see some real analysis. I know anything with racial differences can destroy one's career, so do not include that variable.

I would include gender because it is strange to see increased female suicides. I have worked with some of that data back in the late 1990's (when I was a student at Cornell, and later Georgetown). Only the People's Republic of China had a female suicide rate higher than males, and in general female suicide rates ten to be very low, and they usually occur among mentally impaired individuals. Seeing that number increase is frightening in and of itself. There does seem to be a real crises in mental health with at least US females. It would be interesting to have some idea why.

Mostly though, it would be nice to see some analysis with some interesting or not correlations. Upper and middle class young men commit suicide. It is an unfortunate aspect of modern life in the West as well as in the developed countries of East Asia. We put a lot of pressure on men, and in multicultural countries the gains of minorities and women have come at the expense of majority men, but we have decided that we want that, so we must accept that consequences. The women are more of a concern. The low birthrates in developed countries are deeply concerning. Increased suicide rates and low birthrates would be a disaster. Perhaps the US could ride it out with increased female immigration, but most other countries simply could not cope.