An Alternative Explanation to the "It's the Phones" Hypothesis that Deserves Attention

TL;DR

The interactive combination of (1) increased healthcare coverage, healthcare utilization, and mental health screenings, (2) expanded protections for behavioral healthcare, (3) reduced stigma of mental health, and (4) changing coding practices and diagnostic criteria explain a large portion of the observed increase in adolescent mental health problems in the U.S.

Backstory

There’s been an apparent collapse in U.S. adolescent mental health across the past two decades. The timing of this collapse coincides with the proliferation of smartphones and social media. The most popular hypothesis among the general public and the media is that the latter is largely or completely responsible for the former. Leading proponents of the “it’s the phones” hypothesis, like Jonathan Haidt, have repeatedly dismissed alternative explanations, like the opioid epidemic, economic hardship and social isolation, because they "do not fit the facts.”

While I believe that Haidt is too quick to dismiss these alternative explanations and fails to adequately contend with the complex, multi-causal nature of mental health, there is an alternative explanation that—despite being highly plausible—has flown under the radar: that the recent observed rise in adolescent mental health problems is due, at least in part, to changes in healthcare, health insurance, mental health screening, mental health stigma, and coding/diagnostic practices. I illustrate this in more detail below, but people tend to forget that there have been massive changes in healthcare—especially behavioral healthcare—over the past two decades, and the nature and timing of those changes make a compelling case for explaining (at least in part) the observed increase in mental health problems among U.S. adolescents.

The best treatment to date of this alternative explanation is made by Adriana Corredor-Waldron and Janet Currie. In their paper, they found that recent increases in suicide-related hospital visits among New Jersey adolescents are mostly explained by changes in how doctors and clinicians screen for and report suicidality. Zach Rausch, Haidt’s lead researcher, addressed some of the “challenges” the findings of this paper pose for “it’s the phones” hypothesis, but ends up largely dismissing this alternative explanation, writing:

Taking all of the contradictions together, it is clear that in the United States, the UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, more adolescent girls are going to the emergency department for self-harm episodes and/or being hospitalized for self-harming behavior. The international pattern cannot be explained by American changes in insurance policies or screening, nor can it be explained by changes in the DSM (which were related to anxiety and depression) or the shift from ICD-9 to 10 because all of this started before the ICD-10 came into effect.

However, I believe that the “massive changes in healthcare” alternative explanation deserves much more attention and a more robust treatment by Haidt/Rausch. In the remainder of this post, I expand on Corredor-Waldron and Currie’s work to make the case that the interactive combination of (1) increased healthcare coverage, healthcare utilization, and mental health screenings, (2) expanded protections for behavioral healthcare, and (3) changing coding practices and diagnostic criteria explain a large portion of the observed increase in adolescent mental health problems in the U.S.

Massive Changes in Healthcare, Explained

I created the gif below to illustrate how the timing of various healthcare-related changes lines up with the observed trends in adolescent mental health problems. The trend lines show the rate of emergency room visits for self-harm (solid lines, left-axis) and self-reported depression (dashed lines, right-axis) among U.S. adolescents. The gif cycles through annotations describing when pertinent policies were implemented, coding changes were enacted, screening recommendations were made, or coverage was expanded1.

For those that would rather flip through the frames of the gif on their own pace:

Why would expanded healthcare coverage and behavioral health protections lead to an increase in rates of ER visits for self-harm and self-reported depression among adolescents?

The implementation of the MHPAEA and ACA in back-to-back years (2009 and 2010, respectively) made huge changes to behavioral healthcare (including mental health). Prior to these policies, behavioral2 healthcare and coverage was often very inadequate. Health insurance policies, if they offered coverage for behavioral health conditions at all, would frequently impose limitations on behavioral benefits that made treatment for behavioral health conditions unaffordable and inaccessible for many families. Additionally, insurance companies could deny coverage for pre-existing conditions, even to children. Combined, these practices created a large disincentive for families to seek behavioral care for fear that they would get stuck with a large out-of-pocket expense and/or a diagnosis that would become a “pre-existing condition” that would be excluded from future coverage if they switched health plans. The MHPAEA and the ACA, especially, required that behavioral health benefits be no different from medical/surgical benefits on health plans, and prohibited denying coverage for pre-existing conditions. The ACA established behavioral treatment—as well as emergency and inpatient services—as “essential benefits” that had to be covered by all plans.

In addition to expanding coverage for behavioral healthcare specifically, the ACA increased the affordability and accessibility of health insurance coverage in general. By 2015, twenty-nine states (plus Washington D.C. ), including many of the most populous states, had expanded Medicaid. In addition to Medicaid expansion, the ACA established the Health Insurance Marketplace in late 2013, which allowed individuals and small businesses to enroll in affordable “qualified” health plans, meaning that they abided by the requirements under the ACA (e.g., covering essential benefits and following established limits on cost-sharing).

Taken together, these changes make it much more likely that a family would seek out and obtain treatment for a child’s behavioral health condition(s). Before the MHPAEA and the ACA, a family may not want to run the risk of getting hit with a huge out-of-pocket expense if they seek treatment for the child’s behavioral health needs. And this applies to both acute (ER and inpatient) and non-acute (outpatient) services3. If, for instance, the child is depressed and engaging in non-suicidal self-injury (such as superficial cutting), the financial risk involved with taking the child to the ER—where they would receive expensive emergency services and possibly even more expensive inpatient services in addition—is just too high to take. Better to keep a close eye on the child at home and try to do the best they can without professional help. But after the MHPAEA and the ACA, families can be (more) certain that they won’t be financially ruined if they take their child to the ER for a behavioral health concern—the huge disincentives to seek out and obtain treatment for children’s behavioral health needs are removed.

Why would expanded screening lead to an increase in rates of ER visits for self-harm and self-reported depression among adolescents?

In addition to the expanded healthcare coverage and behavioral health protections that I described above, the ACA mandated that all preventative care, including yearly check-ups with the pediatrician, be totally free of cost. At the same time, governing healthcare bodies such as the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended that adolescents’ mental health be screened for things like depression and suicidal ideation. Specifically, in August of 2011, HHS published the Women's Preventive Services Guidelines which recommended that girls aged 12 and older be screened annually for depression. In 2018, the AAP recommended all pediatricians screen for depression and include suicide-related questions in children’s annual wellness visits.

The combination of all these factors means that, starting around 2011, more kids were getting preventative services (like yearly pediatric check-ups), and at those check-ups those kids were getting screened for things like depression and suicide. More check-ups, more screenings, and more protections for behavioral health conditions leads to lots of kids screening positive for depression and getting diagnosed—helping to explain the rise in self-reported depression since 2011. The depression and self-harm screenings also lead to catching more severe cases, which helps explain the rise in ER visits for self-harm since 2009. As described by Plemmons and team in their 2018 Pediatrics article,

Only a minority of pediatricians report that they feel comfortable treating depression. If pediatricians are screening patients for depression and [suicidal ideation] more often but are not equipped to manage these conditions, they may be more likely to refer these patients to higher levels of care, including children’s hospitals, to access mental health care.

So we have a situation where more kids are coming in for annual check-ups, leading to more screenings for depression and self-harm, leading to more positive screens for depression and/or self-harm, but pediatricians are not adequately equipped to handle mental health issues—especially self-harm—so they opt to send kids to the ER and have the hospital take care of it. And because the family knows they have coverage for behavioral health services, emergency services, and inpatient services, they are much more willing to take their kid to the ER as the doctor recommended.

Additionally, a byproduct of the increased protections for behavioral healthcare and screenings for mental health issues is that kids (and their parents) are more comfortable talking about and seeking treatment for behavioral health issues. The removal of the disincentives to seek behavioral health services combined with an expanding awareness of the importance of mental health, especially among kids, reduces the associated stigma substantially. Over time, the network effects further reduce stigma, increasing the likelihood of kids disclosing their mental health issues to others. Behavioral health services are more available, more accessible, and more affordable. And kids, their pediatricians, and their parents are more sensitive to potential behavioral health issues. This is a recipe for increased self-reporting of depression and ER visits for self-harm.

Why is the rise in self-harm ER visits and self-reported depression concentrated among adolescent girls?

For depression, as I described above, HHS published guidelines in mid-2011 that included the recommendation that all girls aged 12+ be screened annually for depression. This helps explain why, after several years of being flat, the trend of self-reported depression started increasing for girls after 2011. These guidelines did not provide recommendations for boys, which helps explain why the trend for boys remained flat during the time that the girls’ went up.

For ER visits, girls are more likely to engage in non-fatal suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury (e.g., cutting) than boys, and these behaviors typically onset (and peak) in adolescence. Women (and girls) are generally more likely to disclose and seek help for mental health issues than men (and boys).

Together, these factors plausibly explain why the observed trend in reported depression and ER visits for self-harm is higher among girls than boys. Girls were more likely to get screened for mental health issues, more likely to disclose mental health issues, and more likely to engage in the type of severe behavior that would get referred to the ER.

Before You Start Moving Those Goalposts…

I believe it’s shifting the goalposts a bit to try to dismiss the argument laid out in this post by saying: “well, these massive changes in healthcare can’t explain observed trends in other countries!” It’s absurd to expect one thing to explain something as complex as international variation in adolescent mental health trends. But, because I expect that Haidt/Rausch will respond to this post (if they respond at all) by trying to play this card, I want to be sure to say: their own hypothesis (“it’s the phones”) doesn’t hold up to this level of scrutiny either (unless you’re doing a bit of cherrypicking, of course). As Tobias Dienlin points out in this blog post, the kids seem to be doing alright in many places around the world where they have plenty of access to smartphones and social media:

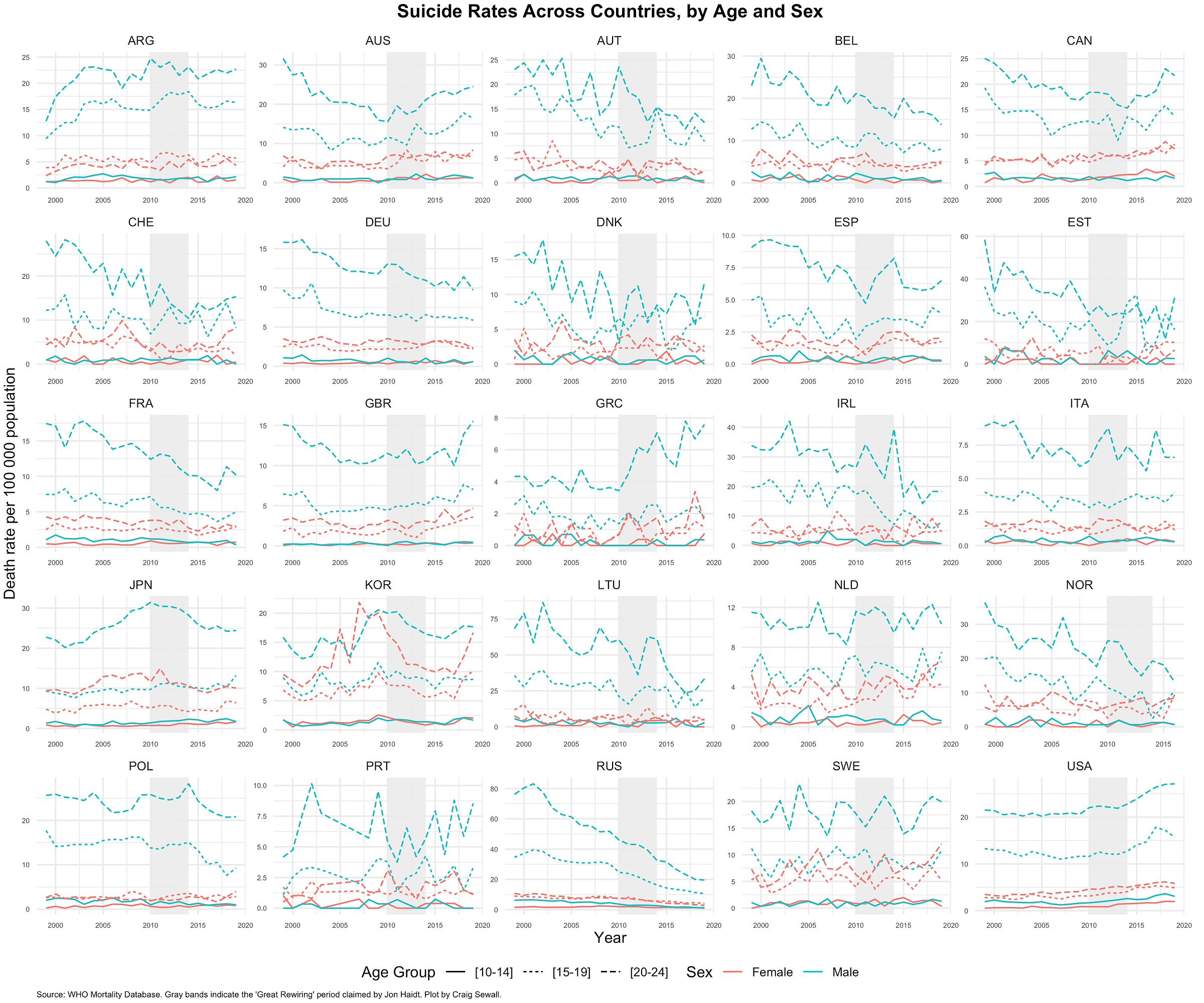

And for an important mental health outcome that is not self-reported, take a look at the adolescent suicide rates for a selection of countries 25 countries below. Some trends line up with Haidt’s hypothesis, but many do not:

This, combined with Tobias’ post above on self-reported mental health outcomes, should be enough for Haidt to at least hesitate before dismissing an alternative explanation because it fails account for mental health trends in other countries.

Conclusion

My goal for this post was to make a case for a plausible alternative explanation to the “it’s the phones” hypothesis. I outlined how the massive, interactive changes to healthcare and health insurance (especially with respect to behavioral health) and mental health screening/reporting could account for the observed decline in mental health among U.S. adolescents, at least in part.

Leading proponents of the “it’s the phones” hypothesis tend to be overly reliant on unicausal4 explanations (particularly their own) and overly dismissive of potential alternative explanations. Is it possible that the invention and proliferation of the internet has been hugely disruptive to societies all over the world in various observed and unobserved ways, including mental health, and that these disruptions have differential impacts across ages, genders, and societies? Of course! I think it’s ridiculous to argue that it has not. So, of course the internet, in general, and social media/smartphones, in particular, could have contributed to the rise in mental health problems among U.S. youth. But there’s also an obvious case that the massive changes to behavioral healthcare and everything related to it that occurred at the same time as the observed trend have a lot to do with it, too.

I don’t love this term, but it’s commonly accepted that “behavioral health conditions” refers to both substance use and mental health disorders

This is one of the ways that Zach Rausch’s recent response to critiques is based on a bad assumption. In the post, Zach claims that changing norms and willingness to seek help may explain part of the rise in ER visits among U.S. teens for self-harm, but they don’t explain the rise in hospitalizations for self-harm because of the time, money, and resources required. But I think the changes brought about by the MHPAEA and the ACA, which were enacted at the exact moment when hospitalizations for self-harm among girls took off, make a compelling case that Zach’s assumption is misplaced here. First, thanks to the MHPAEA and the ACA, many more families would be willing to take their kid to the hospital for behavioral concerns—especially if the concerns were severe (e.g., suicidal ideation, self-injury). Second, hospitals would be more willing to hospitalize kids for behavioral concerns because they know they will get reimbursed for it. Hospitals are more likely to avoid providing services, especially expensive services like inpatient care, if they are unsure if those services will be paid for. So patients with inadequate coverage (or no coverage at all) are less likely to be admitted.

Or quasi-unicausal for Haidt. He does talk about another factor being the decline of a play-based childhood. But it sure seems like he spends most of his time and energy talking about the phones.

What kind of data is available for 2005-2006 range? That was the first depression / suicidality moral panic re: the Internet that I remember. That may have been a total media invention though.

Here's an observational take. I've taught at the same high school for the past twenty years. The student population is largely upper middle class, and well insured. The onset of the ACA had little to no impact on my students. The trend I first noticed, back in 2016 or so, was an increase in students missing school for anxiety. I still remember the first student I had who had missed multiple days of school. When I asked her what was wrong, she explained she was too anxious to come to school. This was unusual. In the past when students had missed school for illness, they'd come back the next day still with a runny nose or on crutches. Now this is a regular occurrence. I regularly hear from students, mostly girls, that their panic attacks and depression are what are keeping them home. Some of these students have missed over 50% of my class this year. It's dire.