Responding to Comments Regarding the Expanded Behavioral Healthcare and Screenings Alternative Explanation

Backstory

, Jonathan Haidt’s lead researcher for The Anxious Generation, posted some comments and questions in response to my recent post describing a plausible alternative explanation for the recent rise in mental health problems among US youth. I started responding to Zach’s comment with a comment of my own, but was not able to post images or links (plus it was getting rather long for a comment), so I decided to just make my response its own post. Besides, I imagine there are other people out there who have similar questions as Zach, so hopefully this makes it more accessible. I’ve included Zach’s comments/questions in full below (in bold) with my responses for each underneath. My thanks to Zach for his thoughtful engagement with the post.

Zach’s Comments & My Responses

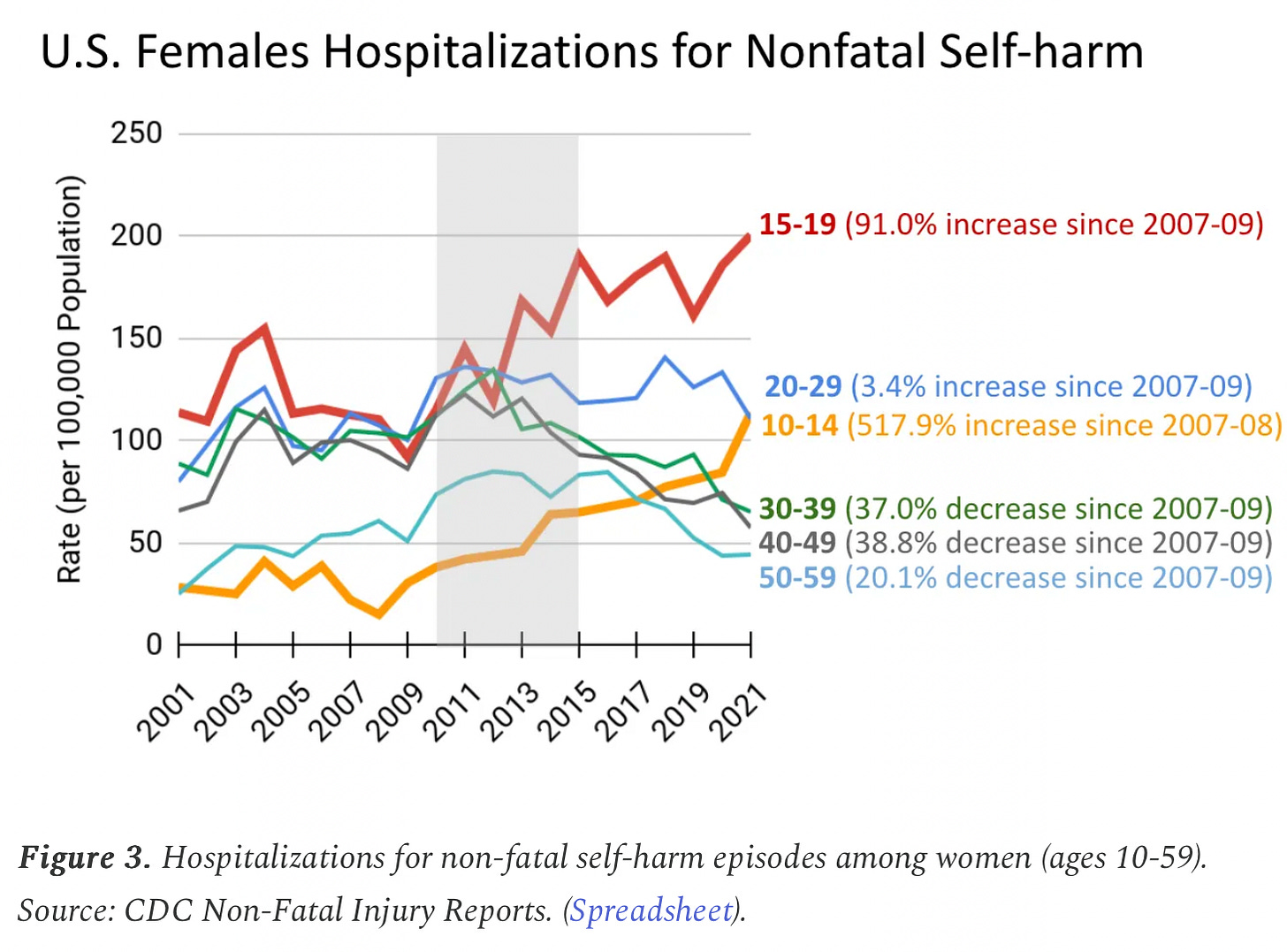

1. I certainly don't doubt that the changes had some impact, but the degree to which you are attributing is definitely more than my sense of what the data reflects. There are a number of points in my post that weren't addressed here (including why self-harm hospitalization rates went down for other age groups, while only going up for adolescents; and some other points). Also, see Jean's recent post on this topic: https://www.generationtechblog.com/p/is-the-adolescent-mental-health-crisis. She'll be opening up the post on Tuesday (so no more paywall).

Non-suicidal self-injury is more common among female adolescents than any other demographic group. So I believe that could explain a large portion of why the rate of ER visits for self-harm went up for adolescent girls while for other female age groups it did not.

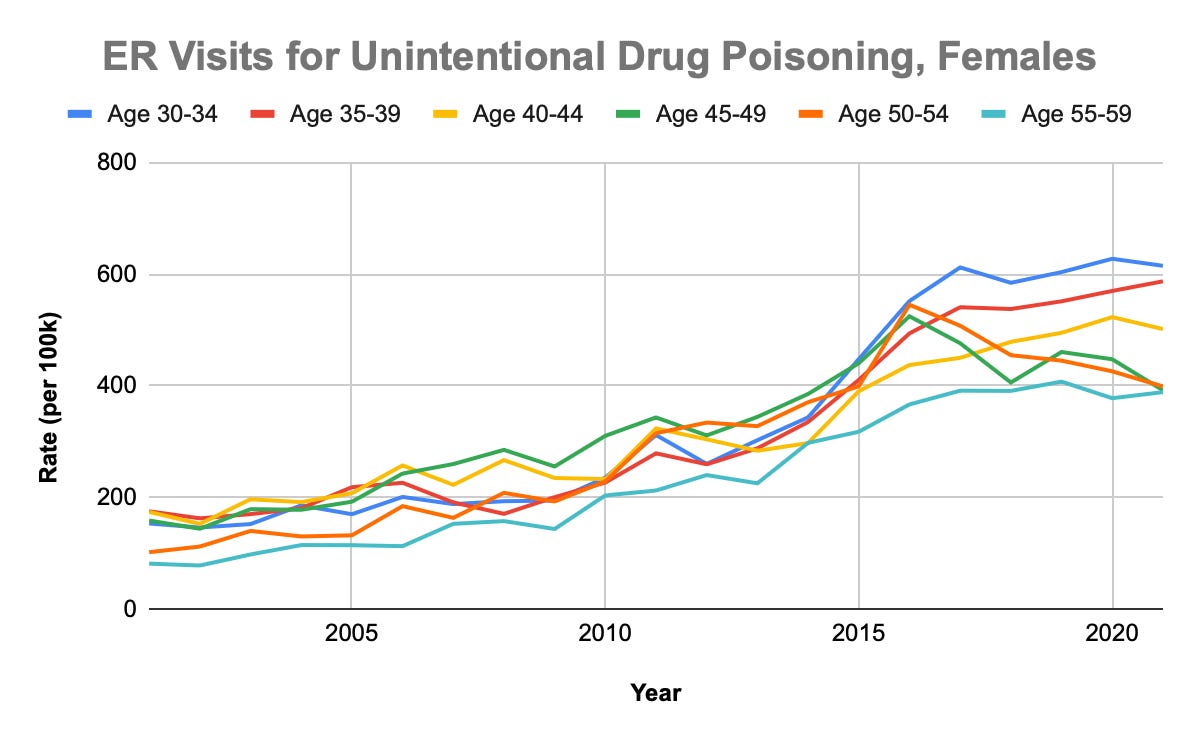

As far as why rates of self-harm went down for older female age groups, I believe this has a lot to do with the opioid epidemic—rates of ER visits for non-intentional ODs went up for middle-aged females at the same time that ER visits for self-harm went down for these groups:

Compare the chart above to the one included in Zach’s post, showing the decline in ER visits for self-harm among middle-aged females. The trends are almost perfect mirror images of each other:

However, I'm confused why Zach is pointing out that ER visits went down for middle-aged females as they went up for adolescent females. Couldn't I then make the argument that the proliferation of social media and smartphones led to a decline in self-harm among middle-aged females? Don't they use smartphone and social media too? Is Zach’s theory that social media and smartphones cause an increase in self-harm among adolescent girls but a decrease in self-harm among middle-aged women?

As far as Twenge’s post, I’m writing this Monday night so I don’t have access to the free version yet. I’ll try to circle back to it later once it’s freely available.

2. If there was more screening and *more treatment* for depression after 2011, shouldn't that drive depression rates down, not up? (especially over longer periods of time). Treatment should work, so if more teens were getting treated, there should be less depression. If "Behavioral health services are more available, more accessible, and more affordable." Would this imply that behavioral health services are making teen mental health worse instead of better? Do you disagree?

A couple things here. First, Zach is talking about a within-person process (person A gets diagnosed with depression, gets treated, and over time their depression symptoms reduce in severity), but the NSDUH data reflect a between-person phenomenon (different people are being surveyed across time). This is classic Simpson's Paradox territory. Also, you have to consider the network effects—more teens getting diagnosed and treated for depression could lead to more teens getting diagnosed and treated for depression (and so on) via reduced stigma, expanded awareness, or even contagion-like effects.

Second, depression is not a simple, monolithic disease where you have it, get treated for it, and are cured. Many forms of depression are recurrent. So, even in the scenario where your depression was successfully treated to the point of full remission (which is rare), it could come back a month or a year later. Additionally many forms of depression are persistent. So, in many instances the severity of the depressive is reduced but not completely alleviated—meaning that certain symptoms have improved while others persist. Third, Zach is right when he says "treatment should work," but in many cases it does not. For some it could make things much better (i.e., full remission), for some it could make things a little bit better, for some it could have no impact, and for some it could have a negative impact. The last possibility, where treatment actually makes things worse, has started to gain attention (cf. "Bad Therapy" by Abigail Shrier) and is another compelling alternative explanation to the “it’s the phones” hypothesis that is also highly compatible with the “expanded behavioral healthcare and screenings” alternative explanation.

This same thing happened with autism. The number of US children diagnosed with autism in 2010 was 1 in 68; in 2020 it was 1 in 36. Now substitute the word “autism” for “depression” in Zach’s comment: “If there was more screening and *more treatment* for [autism] after 2011, shouldn't that drive [autism] rates down, not up? (especially over longer periods of time). Treatment should work, so if more teens were getting treated, there should be less [autism].” I’m not very convinced by this line of argument.

3. You say: "More check-ups, more screenings, and more protections for behavioral health conditions leads to lots of kids screening positive for depression and getting diagnosed—helping to explain the rise in self-reported depression since 2011." I am not sure how this applies to the NSDUH because it is not asking about diagnoses. It's using the DSM symptoms of depression, including symptoms that some of people (perhaps especially teens) don't know are linked to depression (like insomnia, weight loss/gain, and fatigue).

I might be failing to fully understand the nature of Zach’s comment here, so please correct me if I misunderstood. But I don’t understand how asking about symptoms vs diagnoses makes a difference with respect to my argument. The depression screening tools used during pediatric check-ups are probably similar to (or the same as) the items used to measure depression in the NSDUH. During a time of increased behavioral healthcare, mental health screenings and mental health awareness, kids are going to be more likely to disclose their emotional/mental health issues, whether it’s to a clinician or a survey.

Also, with the NSDUH, mental health got worse across all socioeconomic groups -- the rise is similar across all income brackets. If insurance/screening was the driving force for mental health increases, I would expect that the uptick should have been concentrated by income.

I’m not sure why Zach would “expect that the uptick should have been concentrated by income.” Between the MHPAEA and the ACA, all types of health insurance from commercial plans to medicaid were impacted. So middle class kids on their parent’s commercial health plan would have expanded behavioral health protections as well as kids on Medicaid. Hence, “mental health got worse across all socioeconomic groups” makes sense.

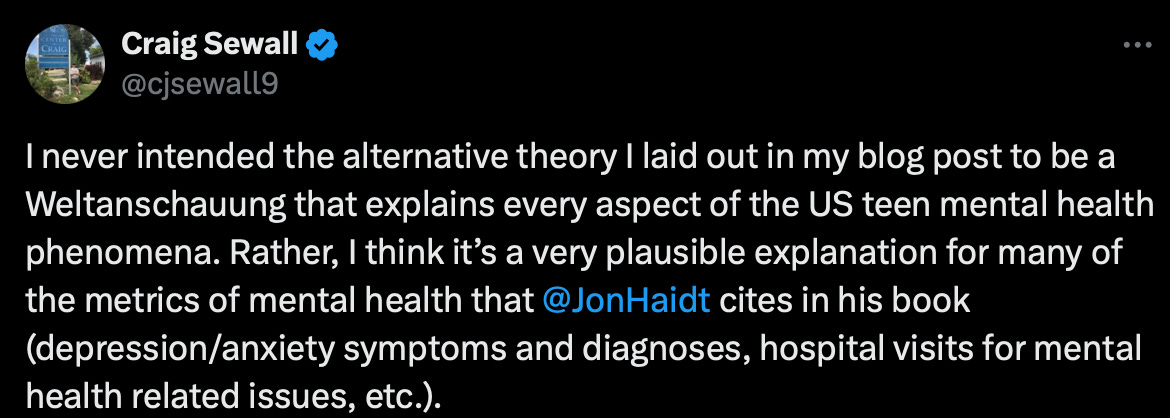

4. There is also data from many other sources showing worsening trends in the U.S.: We find that there is less life satisfaction, less happiness, and lower expectations for the future, along with more kids reporting feelings of meaninglessness and uselessness. (All of which Monitoring the Future data is showing). All are correlated with depression but aren't exactly the same thing. Is this just a coincidence with the increase of screening?

I just want to reiterate what I wrote in this Twitter post:

In addition to what I wrote in the Tweet above, the point of my original post describing this alternative explanation is not to claim that the observed surge in adolescent mental health problems is not real. Rather, I believe it’s highly likely that the observed increase in adolescent mental health problems in the US is partly due to changes in coverage/stigma/screening and partly due to actual worsening of adolescent’s mental health at the population average level. This whole “debate” around whether “it’s the phones” or not is so rife with all-or-nothing thinking. Either my theory is true or it’s not. Either Haidt’s theory is true or it’s not. All these are false dichotomies. The causes of something as complicated as international variation in adolescent mental health trends is going to have multiple causes/explanations. Anyone who tells you otherwise is trying to sell you something.

With all that being said, I think that the worsening trends in the mental/emotional health that Zach references in his comment are due, in part, to actual decrements in well-being at the population average level. However, the constructs that Zach mentioned—uselessness/meaninglessness, life satisfaction, expectations for the future—are classic features of depression. Again, Zach seems to fall into the assumption that depression is a monolithic thing. In addition to the heterogeneous courses that clinical depression can take (as I explained in response to comment #2 above), the definition and measurement of depression as a clinical construct is also highly heterogeneous. As nicely explained in this blog post by Eiko Fried, there are a ton of different ways of measuring different aspects of depression. So by saying “all are correlated with depression but aren’t exactly the same thing,” Zach is merely echoing the messy psychometric process of capturing fuzzy, latent constructs like depression.

5. I have a lot to say about the international data, and this is something I am currently working on. I think that you are underplaying the theory we are putting forth, which *is not uni-causal*. The loss of the play-based childhood is essential; and the "play-based childhood" I think is often misunderstood and simplified to only apply to play itself (which is a reasonable.. as the name does not fully encompass what I see it entailing). it applies to a broader social ecosystem, something I'm starting to call a "community-based childhood." (this includes mentorship, guidance, trusted adults, rites of passage, etc.). This is central to Chapter 4 of the book. New technologies (and other social forces) have long been pulling individuals away from local place-based relationships, real world communities and groups, which drive reduction in local social trust and unsupervised play. This leaves physically isolated kids in an isolating online world without a community of real world support around them. All of this is part of the story. And there is a lot of cultural variation in the tightness and enmeshment of real world communities, and relationships with technology.

I think this is an example of how Zach and Haidt engage in HARKing (Hypothesizing After the Results are Known), which I first pointed out in this Twitter thread (which is a bit snarkier at times than I wanted it to be—my apologies to Zach and Haidt). Their initial theory runs into some issues—i.e., numerous countries where social media and smartphones are ubiquitous among youth do not display the kind of mental health trends as observed in the US—so they dredge the data for patterns and then weave a story together post-hoc that makes it make sense.

It’s also an example of how Zach and Haidt’s vague, narrative-driven, verbal theories are extremely hard to pin down and why I challenged them in this post to provide a DAG (or some other clear, precise representation of their causal model) of the data generating process so that it could be tested by the scientific community. To my knowledge, they still have not yet provided such a model.

6. Also see this study by David Blanchflower, on some new international data https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w32337/w32337.pdf

Caveat: I have only quickly skimmed this paper, but a few things immediately stood out to me. First, David Blanchflower loves him some David Blanchflower. I counted 21(!) self-citations, which accounts for nearly 1/3rd of the 68 references included in the paper. Blanchflower also likes to cite Jean Twenge’s work in his paper but for some reason fails to cite Amy Orben and Andrew Przybylski’s work, despite the fact that the latter group’s work on the question of screen time and adolescent mental health tended to be much more transparent and robust than the former. Perhaps as I dive deeper into the paper I’ll find reasons for appreciating it. But there are a few red flags that already got my hackles up.

Conclusion

Again, I appreciate Zach’s comments/questions pushing back on my post making the case for expanded behavioral healthcare and screening as an alternative explanation for the recent rise in adolescent mental health problems in the US. I welcome Zach’s (and anyone else’s) feedback on this or the original post. Thanks for reading!

Thanks for this Craig. Will respond when I have some time.