How a Tech Panic is Born

Using the exemplar of autism to show how changes in healthcare, diagnostic standards, and screening practices can clearly account for changes in prevalence (but it's much more fun to blame it on tech)

Background

A week or two ago, I published a post where I made the case that changes in healthcare coverage, mental health screening and awareness, and diagnostic coding practices are a plausible alternative explanation to the “it’s the phones” theory for the observed rise in mental health issues among U.S. youth. Unfortunately, it appears as though the leading proponents of the “it’s the phones” theory (Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge) remain unmoved by this alternative explanation, despite its plausibility.

So, the purpose of today’s post is twofold: (1) reinforce how changes in healthcare coverage, screening and reporting practices, diagnostic standards, and awareness can plainly account for significant increases in the prevalence of a certain condition, and (2) illustrate how easy it is to mislead people into thinking that the predominant reason for that rise is the proliferation of new technology.

The Exemplar of Autism

Why Autism?

Autism is a neurological and developmental disorder that is characterized by behavioral, social, and communicative impairments that typically appear early on in life (before age 2). Although symptoms usually appear early on, it may not be diagnosed until later in a child’s life (if at all). The level of impairment associated with autism varies from mild (e.g., Asperger’s) to severe, which is why the official diagnosis for autism in the most recent version of the DSM (the manual for diagnosing and classifying mental disorders) is called “Autism Spectrum Disorder.”

Autism is an organic and chronic disorder, meaning that it is caused by genetic and/or neurobiological factors rather than psychological and/or environmental factors, and it’s typically a lifelong condition—although services and treatments can help reduce impairment. This is important, as autism provides a clear contrast with anxiety and depression (the disorders that Haidt/Twenge like to focus on), which tend to manifest in adolescence, are episodic in course, and are much more influenced by environmental factors (e.g., family- or school-related distress).

So, when looking at long-term trends in the prevalence of these disorders, it’s implausible that changes in social/environmental factors would be (largely) responsible for changes in observed rates of autism. But it’s highly plausible that changes in social/environmental factors would be (largely) responsible for changes in observed rates of depression/anxiety. So the case of autism provides a type of negative control that makes it easier to see how changes in screening, diagnostic standards, etc. impact observed changes in prevalence.

In other words, changes in observed prevalence of anxiety/depression could be due to changes in social/environmental conditions (e.g., “it’s the phones”) or “other things” such as changes in healthcare, awareness, screening and diagnostic practices, etc. Whereas changes in observed prevalence of autism could only (or mostly) be due to those “other things.”

Autism Prevalence Over the Years

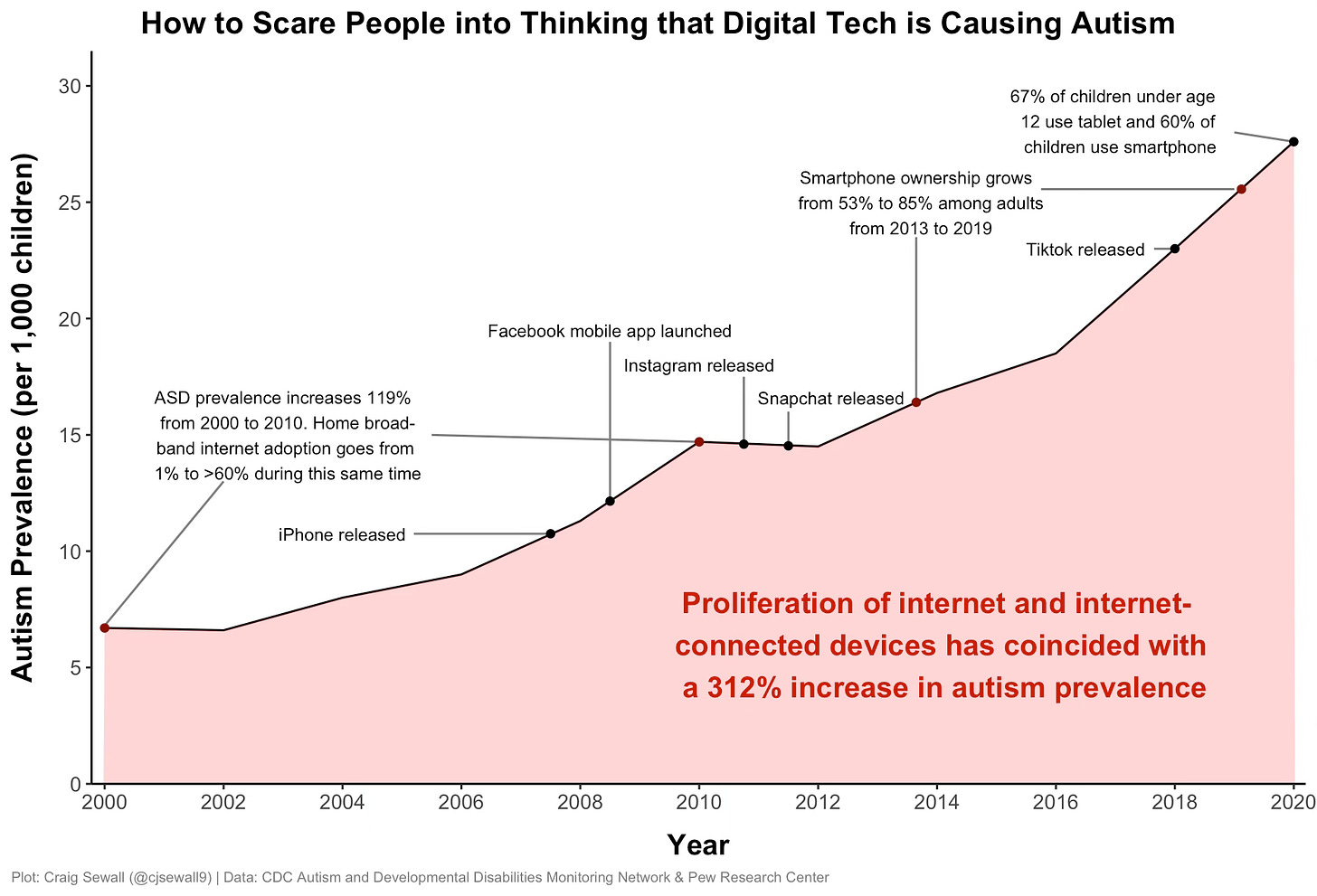

I created the chart below to illustrate how the prevalence of autism has skyrocketed over the past half-century and how changes in diagnostic standards, screening and reporting practices, awareness, and healthcare can explain the observed rise:

As you can see, autism was fairly rare until the turn of the century, when the diagnostic threshold for autism was loosened substantially with the release of the DSM-4 (in 1994), followed closely by the implementation of the Autism Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network (in 2000) which established regular, systematic surveillance of autism prevalence among U.S. children. Prevalence continued to rise after 2002, spurned on by recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics to screen all children for autism during routine visits combined with expanded healthcare coverage and affordability brought on by the implementation of Obamacare. This Scientific American article does a great job of explaining the different events detailed in the above plot and how they contributed to the surge in autism diagnoses among U.S. children. I recommend you check it out.

A Tech Panic is Born

Let’s say that you never saw the plot above or read the Scientific American article detailing how changes in diagnostic standards, autism awareness, and screening recommendations contributed to the massive changes in autism prevalence among U.S. children. All you know is that we’re living in a time of significant change—the internet and its cousins (smartphones, social media, etc.) are everywhere. Life looks (and feels) a lot different than it did in the 1990s or the 1980s.

Then, a popular and respected American psychologist by the name of David McLean comes along, shows you the plot below (but with a different title, obviously) and says, “Did you know that there has been a 312% increase in autism prevalence among U.S. children since the turn of the century?” You think: “Wow, that’s really bad. You know, now that you mentioned it, I have noticed that autism seems to be much more common these days than when I was growing up.” And then David McLean proceeds to tell you a very compelling story—complete with references to academic studies and scientific research and “causality” and all that—explaining how the proliferation of the internet and smartphones and social media are responsible for the surge in autism among our children.

The story is very compelling. It helps make sense of something that you’ve had some vague suspicions about: all this digital tech can’t be good for our kids. He’s got a list of recommendations for how to combat the crisis and they all seem reasonable, especially when you consider how critical the crisis is. And he seems like a trustworthy source—he’s lauded for being a fair and impartial scientist. And the media seems to really respect him—he’s on all the shows and podcasts giving interviews where he talks very eloquently about his theory. And he’s got a bestselling book—which is being endorsed by all sorts of politicians and celebrities.

Given all that, you’re convinced that David McLean is right. The proliferation of internet and smart devices into our homes and jean pockets has literally rewired our kids’ brains, with drastic consequences. You join the movement he’s spearheading. He’s got some detractors, but who doesn’t? They’re probably all bought off by the tech industry. So you pay them no mind.

Conclusion

The point of this post was to use the case of autism to (1) reinforce how changes in healthcare, screening practices, diagnostic standards, reporting methods, and awareness can very plausibly explain changes in observed mental health trends, and (2) illustrate how easy it is to stoke a tech panic. I want to again make it clear that I am not some sort of extreme denialist on this topic—even though folks like Twenge and Haidt like to paint their detractors as such. I believe that the observed rise in mental health problems among U.S. youth deserves our attention and our concern. I also believe that it is utterly foolish to think that something as complicated as mental health can be simplified down to one (or maybe two) factors.

The observed rise in mental health problems among U.S. youth is due to changes in social/environmental factors and “other stuff” like changes in screening/diagnostic practices. Of the social/environmental factors, I believe the “it’s the phones” theory accounts for a small portion. The surge in parental suffering and death is surely an important factor. The prevalence inflation theory probably has something to do with it, too. And a ton of other things that I haven’t mentioned.

The point is: it’s complicated. And beware of people peddling over-simplified theories and solutions to very complex problems. They're almost always trying to sell you something.

Great breakdown. The publication of Donna Williams' "Nobody Nowhere" (1992) and Temple Grandin's "Thinking in Pictures" (1995), both bestselling autobiographies of autistics, as well as the Oscar-winning movie "Rain Man" (1988), have done a lot to influence the public awareness of autism during that initial rise in diagnoses as well. That may have indirectly affected diagnostic rates, as more laypeople learned to recognize and potentially flag the symptoms.

I’m also skeptical of the *literal rewiring* argument and the dismissal of other factors in favor of a blanket “it’s the Internet.”

Another piece of this that a lot of these critics are responding to is an uptick in mental health “culture” that proliferates online. So, not only are phones isolating young people and not only are they comparing themselves constantly, but they’re also entrenched in subcultures which make various mental health diagnoses subcultural signifiers.

I think it’s basically true that this exists and it’s amplified by the media. There seems to be a secondary market of tee shirts, workbooks, wellness regimes etc that are marketed to people who want to be in a digital autism subculture. This is also true for anxiety, depression, etc.

That being said, I don’t love the tack that all of this is an expression of narcissism and that there are easy solutions. On both the cultural and medical dimensions, the conversation feels painfully flattened. Ironically, that, too, is probably a product of the Internet: easier to sell black and white thinking than nuance.